Funny business

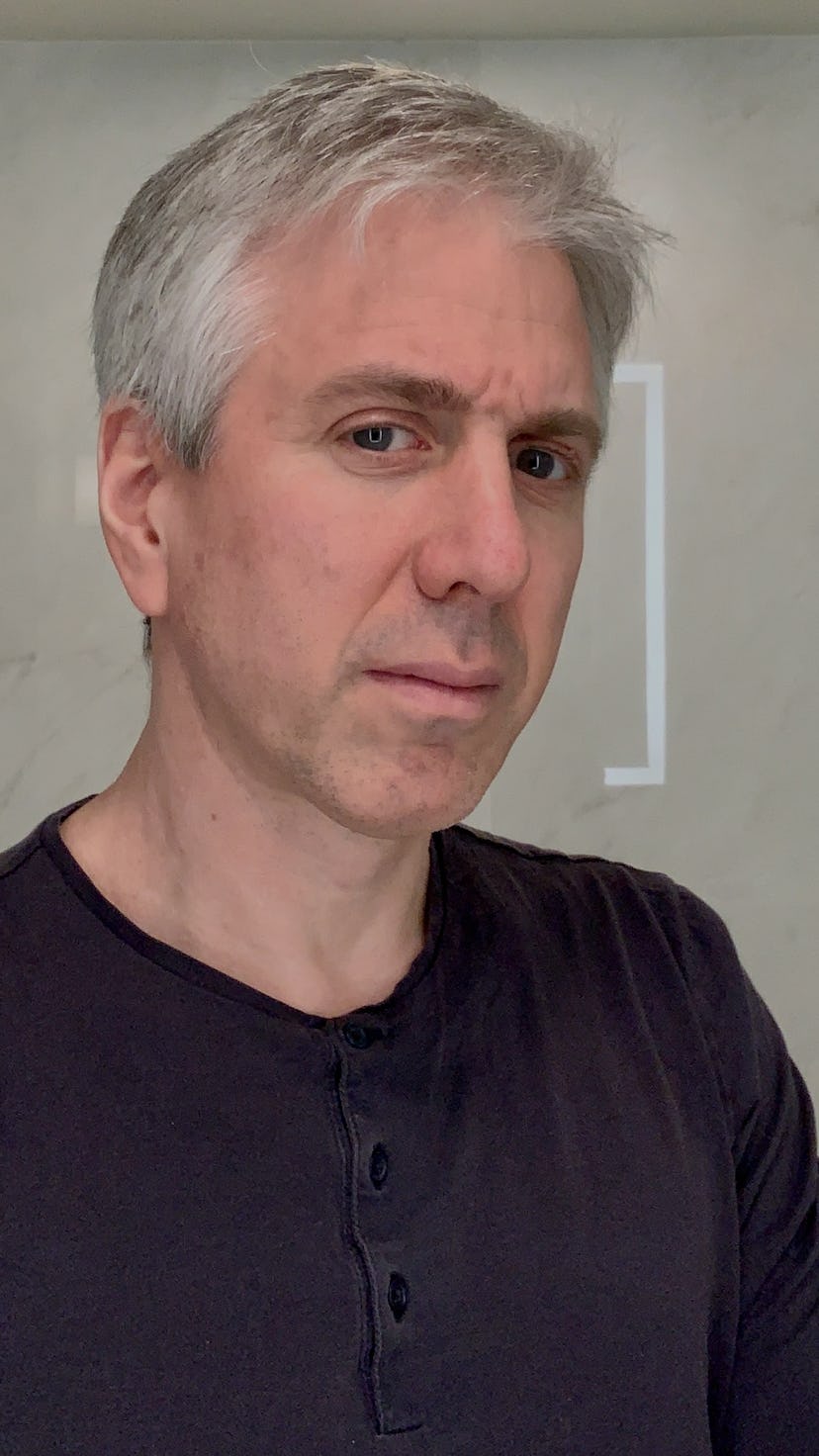

Jeff Price is sick of comedians getting screwed by Pandora and Spotify

The CEO made a career out of getting musicians paid their fair share. Now he’s repping the estates of Robin Williams and George Carlin.

Jeff Price has spent the majority of his working life fighting for the rights of musicians. And now he’s aiming to strike a blow for another group of people he believes have been screwed out of their rightful income: comedians.

On February 7, clients of his — Andrew Dice Clay, Ron White, Bill Engvall, and the estates of the late Robin Williams and George Carlin — filed multi-million dollar lawsuits against Pandora in the Central District of California, claiming the platform has been “willfully” streaming the comedians’ recorded routines without proper licensing.

Williams’ family is seeking $4.1 million in damages, while Carlin’s wants $8.4 million. Price isn’t formally involved in any of the suits — they were filed by lawyer Richard Busch — but he says he and his company have helped clients recognize the money they’re owed.

Price, who is 54 and based in New York, is the CEO and co-founder of Word Collections, a company that licenses streaming rights to music, spoken word, and comedy performances. He began working in the music industry in 1990, when he founded a record label, SpinART Records, with a high school friend. The label released albums from indie acts like the Apples in Stereo and the Pixies.

Price quickly picked up on something that frustrated him more than the legalese in the contracts: the massive disparity in power between artists and those releasing the records. “It just wasn’t fair,” he says. “Typically, ownership of the copyright was transferred from the recording artists to the record label, and on top of that, when the music sold on CD or vinyl, the musician would get something like 12 percent of the money. The rest got kept by the record label.”

Price operated his label differently, splitting net profit 50/50 with musicians. But music is a fickle business, and SpinART sputtered out by the mid-aughts. Around that time, Price decided to enter the burgeoning world of digital music.

He says he soon learned that distributors set up to handle digital music pretended it was far more complicated than it was in order to charge more to the artists they worked with. “I was looking at that, getting very pissed off,” Price says. “You’re not doing what a traditional distributor does — manufacturing and shipping and calling up the retailers and all the other crap. You’re moving a file from point A to point B.”

“Streaming services sort of skipped over comedians — stuck them in a corner and just ignored them — until someone like me turned up.”

Price was taking a shower in his small apartment in New York when he came up with the idea for his company, TuneCore, which would do business better. “I thought, ‘Fuck this, I’m going to create a company that will allow anyone on the planet to distribute their sound recording into the digital music services at the time. They keep ownership of their copyright.’” The artist paid a flat fee for the service, and when the music was streamed, they kept all the income.

When Price left the company in 2012, it had paid more than $1 billion in royalties to musicians. But it could have been more. The artists were paid for some, but not all, elements of their copyright. With a former colleague, Price set up another company, Audiam, which helped artists get back $1.5 billion in what they were due from streaming services. He left that company in mid-2020, and set about helping comedians.

“Even though it’s the exact same copyright [as music], they sort of skipped over comedians — stuck them in a corner and just ignored them — until someone like me turned up,” Price says. He intends on making streaming services pay — and pay big.

Complex jokes

There are two types of copyright associated with a music track, explains Kristelia García, a copyright professor at the University of Colorado Law School. Every song has a copyright on the underlying musical composition — the sheet music and lyrics involved. The actual recorded track has a separate copyright associated with it.

Each part is controlled by different entities that disburse the rights on behalf of artists. Streaming services need to get both in order to stream a track. (That’s why Taylor Swift re-recorded new versions of her songs as part of a dispute with music producer Scooter Braun; by doing so, she cut him out of the rights to any plays of those songs on services like Spotify.)

“When it comes to streaming comedy, it turns out it functions the same way music does: There’s the underlying composition and the recording of it,” says García.

“Platforms have thought, ‘Well, if we pay for the recording, we don’t have to pay for what’s in the recording.’”

However, E. Michael Harrington, an intellectual property consultant specializing in music rights, says that historically streaming services have been paying the owner of the sound recording for comedy sets — usually the record label that releases it — but not the owner of the intellectual property — the jokes — within the recording. “They’ve thought, ‘Well, if we pay for the recording, we don’t have to pay for what’s in the recording,’” Harrington says.

Whether overlooking intellectual property rights comes down to confusion or willful neglect is somethin Busch, the lawyer bringing the five cases against Pandora, doesn’t want to comment on. “What I do feel comfortable saying is that the law requires these licenses for both public performance and reproduction on interactive streaming sites,” he tells Input. “And it appears neither Spotify nor Pandora — nor any of the others — obtained the required licenses.” Pandora and Spotify did not respond to Input’s requests for comment.

Whether deliberate or not, there’s a case to answer. “These interactive streaming sites are multi-billion dollar companies,” says Busch. “And they have not paid my clients in these cases either the appropriate mechanical royalties” — cash due every time an audio track is reproduced — “or public performance royalties,” due when a track is performed or played publicly.

Busch believes he has the streaming services dead to rights — and third-party experts believe that’s the case, too. “I think the lawsuits are pretty cut and dry,” says García. “What I will be interested to see is if they settle, as so many of these cases do, or if it’ll go further.” She believes an out-of-court settlement is likely, as copyright infringement is a strict liability offense: It doesn’t matter whether an organization meant to breach copyright or not. As such, she can’t see any real reputable defense Pandora can mount.

Joseph Fishman, a professor at Vanderbilt University Law School, says that the increased popularity of comedy on streaming services means the question of who owes what “matters now in a way it didn’t used to.”

He adds, “There wasn’t much money in publicly performing recordings of stand-up comedy the way there had historically been for music. Instead, the money came mostly from live gigs, album sales, and TV specials.” Now, however, streaming comedy is an increasingly big driver of revenue for those services, and the piece of the pie is therefore getting larger. Other comedians, including Kevin Hart and John Mulaney, have disputed the amounts they’ve been paid by Spotify.

“They just waited till they got caught with their hand in the cookie jar.”

Both García and Fishman point out that part of the reason streaming services may have not vigorously pursue snapping up all elements of the rights to comedy performances is that there’s not an industry-wide body with whom to negotiate rights like there is with music. Also, in comedy, where jokes are often written by one comic for another, pinpointing who should be paid what can be particularly vexing. Generally, it’s not as easy to pinpoint who the original author of a joke is as it is with a song, says Fishman.

Price says his advocacy for his clients is a matter of principle, not profit. “That’s how we got to where I am today,” he says. “It’s the same thread of there’s a right and there’s a wrong. Some of these companies are worth literally over $3 trillion in the stock market. There’s more money being made off of these recordings and music now than any point in history.

“There’s less of it going back to the creators, and in the case of the comedians, they didn’t even bother to get a fucking license and make a payment, and they knew it,” he says. “They just waited till they got caught with their hand in the cookie jar.”