Marked With Stigma

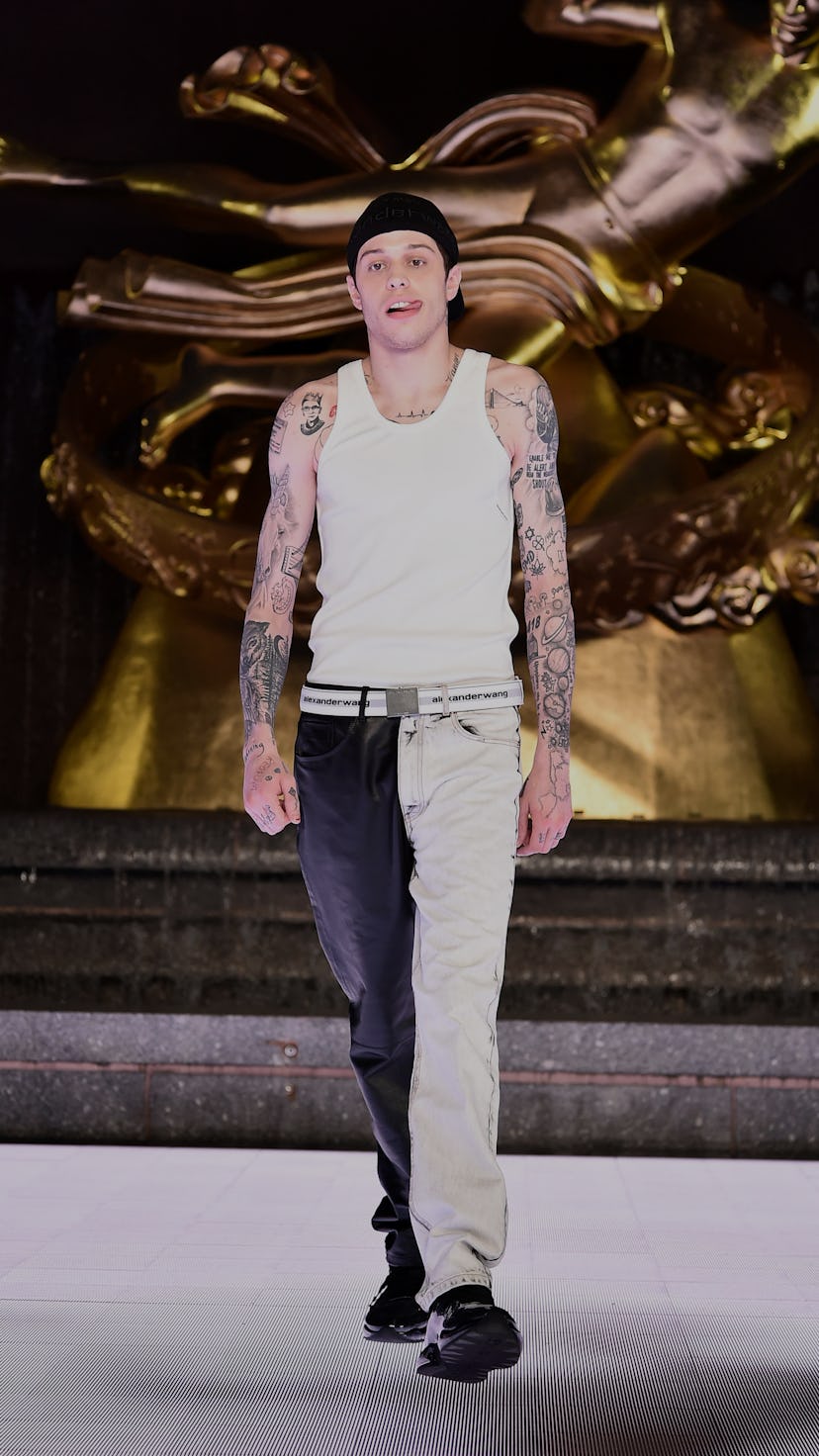

Loved and hated: How the 'wifebeater' became a loaded fashion statement

The shirt was made for sweaty men in the '30s, before turning into a controversial piece. In 2021, it's not exclusive to men — but its terrible name lives on.

Inside or outside the fashion lexicon, it’s hard to think of a term more cringe-worthy than “wifebeater.” So why are we still saying it, let alone wearing it?

The white ribbed tank has been a staple in menswear for nearly a century, and it’s picked up plenty of stereotypes along the way. The cheap undergarment was first associated with classism and domestic violence, but has since spiraled into an ironic piece with a costume-esque level of camp. How has such a hot-button garment managed to survive through generations, without any visible change? Pop culture cameos and fashion subcultures, from Marlon Brando to queer disco, have transformed the wifebeater into an intersectional symbol — and satire — of masculinity.

The wifebeater, originally called the “A-shirt,” was invented in 1935 by sock company Cooper’s Inc. It was intended as an undergarment, to keep sweat from damaging men’s dress shirts. However, for working-class men who couldn’t afford enough dress shirts to wear every day, A-shirts flew solo as a cheap alternative to simply going shirtless.

The origin of the term “wifebeater” is exactly as horrific as it sounds. In 1947, when Detroit man James Hartford Jr. was arrested for beating his wife to death, newspapers published his arrest photo — wearing a blood-stained A-shirt — and captioned it “The Wife Beater.” His gruesome title stuck to the garment itself, and hasn’t left since. Four years later, the wifebeater made its first pop culture appearance, on Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire. Brando’s character, a blue-collar man who abuses his wife, unfortunately sealed the connection between A-shirts and violence.

“Men wearing tanks without a shirt were associated with working class, generally ‘non-respectable’ conditions,” said Jay McCauley Bowstead, a London-based lecturer on fashion and masculinity. “So already, in the term ‘wifebeater,’ we have a problematic and classist elision between proletarian identity and domestic violence.”

“In the term ‘wifebeater,’ we have a problematic and classist elision between proletarian identity and domestic violence.”

Pop culture gradually normalized wearing the wifebeater by itself, by leaning into the sexuality of such a body-hugging piece. Sex symbols of ‘70s rock, like Freddie Mercury and Mick Jagger, wore wifebeaters in their famously form-fitting stage looks. Testosterone-fueled action flicks of the ‘80s (see: Die Hard) showcased leading men in wifebeaters, leaving very little bicep to the imagination. In the ‘90s, the wifebeater joined the exploding rap scene, with legendary frontmen like Tupac wearing them on repeat.

With each decade, the wifebeater touched every point of the masculine spectrum — rockstar costumes, Hollywood action heroes, Compton rappers, and every bodybuilder in between. According to McCauley Bowstead, this diversity is exactly what’s kept it alive, and exactly what menswear needs. “I think the tank occupies an ambiguous role in pop culture because it has such contradictory significations: a military form of manliness, an imagined (sometimes fetishised) working class masculinity, but simultaneously queerness...” he said.

As simple as the A-shirt is, such a revealing garment actually disrupts the heteronormative boundaries of menswear, where men are still gawked at for wearing anything remotely feminine. “Menswear remains more rule-bound than womenswear,” McCauley Bowstead added. “To challenge the norms of menswear is to challenge dominant conceptions of masculinity.”

As the wifebeater built a hyper-masculine persona through pop culture, evolving past (and overcompensating for) its lowly origins, it was only a matter of time before the machismo bubble burst into camp. According to Jessica Glasscock, a fashion history professor at Parsons School of Design, the wifebeater’s lasting life comes from queer subcultures. The garment that once defined masculinity was suddenly defying it, as a tongue in cheek performance piece.

“ It was in the hands of queer culture, decades later, which embraced the shirt as a costume and performance rather than as identification with an abuser.”

“It’s inescapably butch,” said Glasscock. “Wearing a wifebeater implies that you have, or aspire to have, masculine qualities of physical strength and dominance.” When such a basic and affordable garment is so loaded with masculinity — for better or worse — it’s the perfect tool to reclaim and exaggerate those qualities.

“It's a great frame for the objectification of the male body. That’s why Brando’s wifebeater is so compelling; he looked really tasty in that shirt,” said Glasscock, echoing McCauley Bowstead’s point about the distinctly revealing fit of a standalone wifebeater. “If you think of him as Marlon Brando, movie star, not [his character], abuser, it’s totally fine to like it — or it was in the 1950s. And it was in the hands of queer culture, decades later, which embraced the shirt as a costume and performance rather than as identification with an abuser.”

Like its journey through pop culture, the wifebeater bounced between queer micro-aesthetics. In the late ‘70s, “Castro clones” idealized working-class masculinity in wifebeaters, flannels, and Levi’s. As West Hollywood led the ‘80s fitness craze, wifebeaters were the perfect showcase for hard-earned muscles. In the ‘90s, butch lesbians shattered the connection between masculinity and a male body, as women claimed stereotypically masculine markers like cropped hair and wifebeaters. All of these groups embraced the garment as nothing more than a performance of masculinity.

“It’s hard to see the wifebeater without an arched brow,” Glasscock added. Had the queer community not absorbed the wifebeater as a cheeky caricature of manliness, it may have never evolved past its sleazy first impression.

At first glance, the wifebeater might seem like an unkillable cockroach of fashion — but its ability to chameleon through almost a century’s worth of aesthetic evolution isn’t an accident. Through every film cameo, stage costume, and subculture, the wifebeater has grown past its morbid roots to represent the diverse intersectionality of what it means to be masculine.

While it started as a tool of classism, the wifebeater has since fueled a greater paradigm shift in menswear. The only thing it still (desperately) needs is a new name.