New Pioneers

Trash is the new black: Zero Waste Daniel turns scraps into fashion

Meet the designer who wants to dress you for a green world.

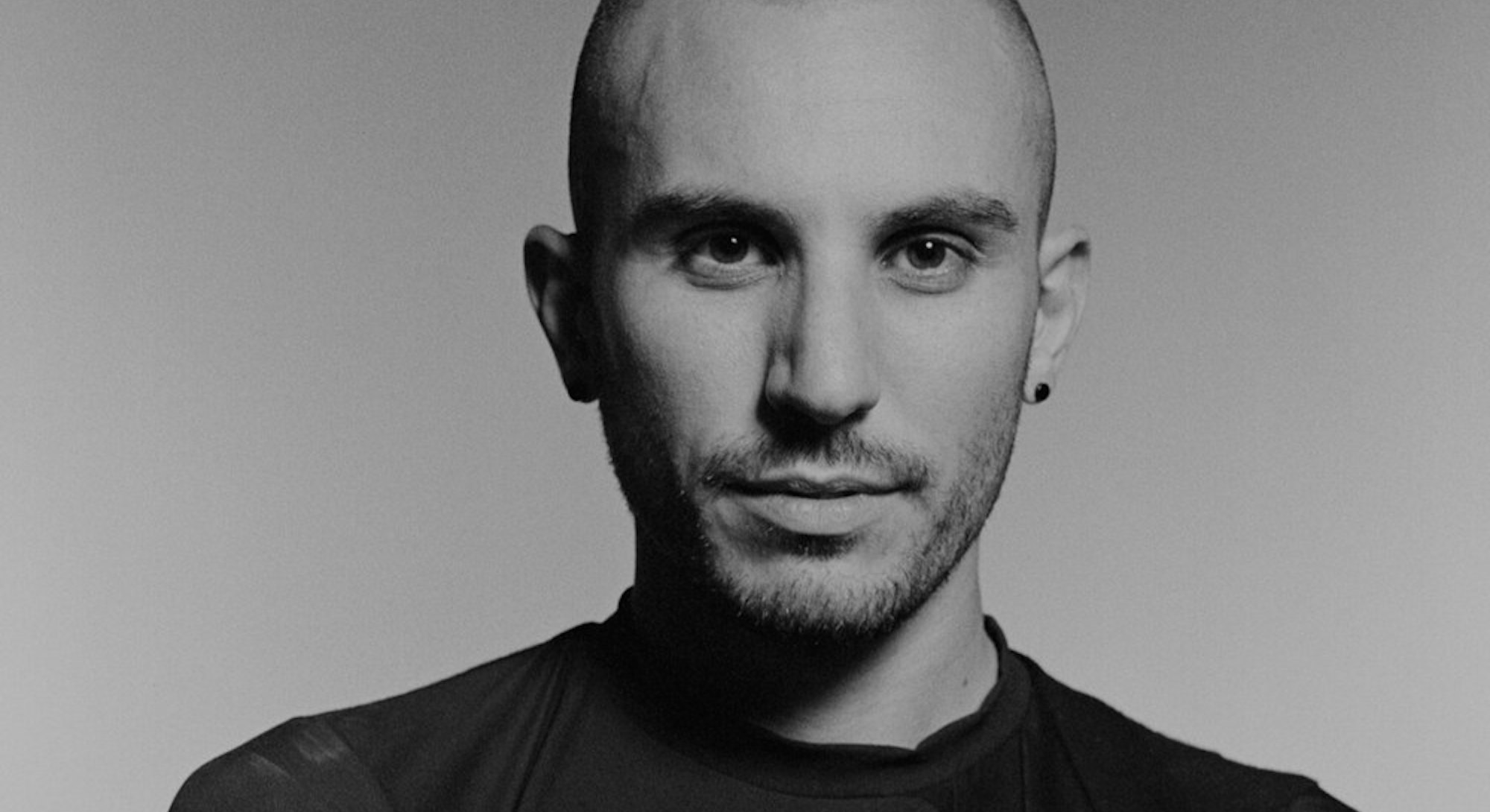

"I think Gen Z, more than anyone, hates being sold things,” designer Daniel Silverstein, founder of the clothing line Zero Waste Daniel, said to me over a video call this week.

“As a fashion company, I have to sell things, but my best tool for doing that is just being honest and communicating. There’s no amount of being an influencer that will ever inspire people to buy things from me. I have to just show them what I'm making and how I make it.” Occasionally, though, someone will insist on the actual patterns. Here, Silverstein, 31, draws the line. “It's hard to be both altruistic and live in a capitalist society,” he said, laughing. “You know? I feel like I’m really walking the line of those two things.”

Silverstein is — literally and figuratively — threading the needle, as he attempts to work ethically in the glamorous industry also notorious for its abuse of workers, models, and the environment, and within the framework of being a small business owner.

Sustainability is increasingly a topic en vogue. In 2018, the UN launched the Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action, where companies like Adidas, Chanel, Nike, and Target committed to “quickly and effectively help implement the Paris Agreement.” It’s estimated the fashion industry is on the hook for 10 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions — more than all maritime shipping and international flights combined — and 20 percent of global wastewater.

What distinguishes Silverstein is his radical zero-waste ethos: each piece of Zero Waste Daniel apparel is entirely made of pre-consumer cutting room scraps, design room waste, and leftover materials that he and his team have collected and sewed back together as patchwork. According to his site, “every piece of ZWD upcycles roughly one pound of textile waste.” The company was rated as “great” — five out of five overall — by ethical fashion monitor Good on You.

Already the subject of a profile in The New York Times, the ZWD origin story is not unknown. Nor is it so uncommon: small-town boy moves to the big city to pursue his dreams, gets disillusioned, then innovates. Upset by all the wasted material he saw firsthand as an intern at Carolina Herrera and Victoria’s Secret, he set out to make a line of his own that might waste less — or not at all. His initial foray, 100% (for how much material is used), was met with some success, though not enough to offset the shuttering of one of his wholesale accounts, which resulted in $30,000 of unpaid orders.

Then one day in 2015, he was ferrying a trash bag of scraps to the dumpster when the bag broke. Throwing out the leftover fabrics would have been “the antithesis of my mission,” he told the Times. Instead, he got to sewing, posted “this dumb selfie of a shirt I’d made out of my own trash because I was too poor to go shopping, and it instantly got 200 likes.” Encouraged by the response, ZWD was born.

Silverstein’s personality — or, as he’s put it, “me talking” — is part of the sell. During our hour-long call, he strikes me as a warm, candid, and thoughtful conversationalist, asking questions and recalling personal details I’d casually mentioned earlier. A natural presenter and performer — he was a contestant on the reality show Fashion Star in 2013 — he started his own fashion-comedy series, Sustainable Fashion Is Hilarious, earlier this year and regularly appears in short videos on the Zero Waste Daniel Instagram account, where he has over 95,000 followers. His “reroll” sweatshirts have been seen on celebrities like Ilana Glazer and Lin-Manuel Miranda; a short documentary about him and his work produced by Now This News has over 15 million views; and he’s even collaborated with the NYC Department of Sanitation.

On a bright morning earlier this week, Silverstein streamed in from his live / work studio in the Bushwick neighborhood of Brooklyn, where he resides with his husband. He wore a gray patchwork hoodie from his striped collection, his laptop perched atop his sewing machine. A painting of Aladdin Sane-era Bowie, a 30th birthday gift from his husband, was visible when he turned the camera to give me a quick tour. Beside him was a stack of cherry red joggers he intended to sew later.

“Making things that I wanted for my life has often been the inspiration for what I'm doing with work.”

James: Do you still have the space in Williamsburg?

Daniel: We closed the retail space, and that was all very much COVID-related. You know, I'm a huge part of our workforce. If I'm in the store helping customers and I get sick, then that's gonna have a huge negative impact on our business. So, for that reason, we had started by just working from the clothes store, because it was also a studio space. Over time, we just saw firsthand the effects of the pandemic on the neighborhood until it got to a point where we felt unsafe. And then we were just like, “If we're not open anyway, why are we paying rent here?” We expanded our home studio to be our main space, which I think is the case for a lot of companies right now. We're actually about to move into a larger space to work and live. But it's not the way I saw any of this going down. I was there almost four years.

One of the other side effects of the pandemic is that I got a puppy. She's kind of freaking out right now. [In a higher voice, to the puppy: “Come on, we have a meeting!”] This is my sewing machine, where she likes to go. And it's her being like, “I can tell you're doing a project...”

James: What have been some of the biggest challenges as an independent fashion designer, working with sustainable clothes in the pandemic?

Daniel: I think the biggest challenge is correlating reality with the internet. All the information that we're getting, you have to process that and then be like, OK, I choose to believe this, I agree with this person usually, so I'm going to agree with their stance on everything that's happening. And then, as an entrepreneur, like, This is the point where I'm going to shelter in place. This is the point where I'm going to not take the subway to my studio but walk to my studio.

Those were a lot of really hard decisions to make, initially. On top of that, things go wrong all the time, even when there's no pandemic. How do I deal with the things that are going wrong and maintain some sort of healthy public persona about my brand without conflating or confusing something going wrong at work with how serious a pandemic is? For a while I felt like I wasn't really entitled to my feelings because things were worse for other people elsewhere.

We had an incident at the beginning of the pandemic where one contractor left, one contractor's studio was closed because it was in a large building, one person's order was messed up, and my only real solution was just to fix it all. And when I didn't have resources, fixing it meant sitting down and sewing, like, hundreds of pieces.

I didn't want to be insensitive. And so I didn't want to say that anything was necessarily going wrong. And I also didn't want to say that everything was great. I just didn't want to talk for a while.

James: I'm curious how you were able to balance being active on social media, because it’s so useful for your business, and just being yourself.

Daniel: I always feel a lot of pressure around Fashion Week. That's the time of year that really irritates me, where it's like, This thing that is my every day is now in the zeitgeist for a week or a month. So I have trouble with that kind of construct to begin with.

When Fashion Week came around this year and we're supposed to be talking about this industry, I sat down to put my thoughts in one place, and I put out almost like an essay, an op-ed kind of piece, on my social media and my Instagram.

When faced with a pandemic, your metric of success is survival. Did I survive this? Or did I succumb to this? It's a binary. Like, I lived through it or I died. I'm looking at my business the same way. My business is either going to survive or it's going to fold in this time.

All of the pinnacle hopes and dreams are on pause, because surviving is the only goal. Once I adopted that mindset, things actually changed a lot for me, because I wasn't so worried about getting a gazillion likes on a post or selling the most I've sold or having the most successful year. I started making decisions that were based around this will be better for my life, this will be better for my business this will be safer for me and my family, this is a better option for my production — whatever it is.

Once we let go of the store — we were like, We don't need this space, we don't need to be in this part of Brooklyn, we're not open to the public, we're just going to focus on our online business — once we did that, our online business started booming in a way that I've never experienced in the five years that I've run this line.

“Things go wrong all the time, even when there’s no pandemic.”

James: How much has the pandemic lockdown affected your gathering operations?

Daniel: Uh, yeah, disaster. [Laughs] Normally, interns are a really robust part of our culture. I take it really seriously. As a fashion intern who worked unpaid, I put a lot of effort into the internship program at ZWD, where we take students based on their interest and education more so than their skills. Every semester we only take people based on applications. But, to give you an example, last summer we had six interns. This summer, we had one. We don't run our business on our interns — we have contractors and factories and all of that stuff for actually making the product, so it hasn't necessarily slowed our production. But it changes our sense of structure.

James: But you're probably making stuff all the time right now because of the rush, right?

Daniel: Leading up to the holidays, it's 14-, 16-hour days of production. It's funny because it's, like, too much of a good thing is never enough. I think we're having this tremendous connection with our online customers right now because they want loungewear, they want masks, they want recycled, they want transparent, they want so many of these things, and we just happen to be in the center of that Venn diagram. We are a lot of things to a lot of people right now.

And even more than just a product, what I see in abundance through our social media is that we're giving people some kind of inspiration right now. People feel highly motivated to pull out their sewing machines and upcycle that thing they never sewed, or start a hobby, or change careers. And they're finding themselves with an enormous amount of time. And because of the last three or four years of media that we've been putting out through our Instagram and other interviews, we're having a boom of discovery right now. I'm getting messages like, “My son started sewing because of you” or “I'm going to upcycle” and people send me photos of their projects that they're working on: “I made my own Zero Waste Daniel.” To me, that is so exciting.

“Instead of being this $1,700, $75,000 crazy, one-of-a-kind, unaffordable piece, it’s a $25 mask that this person is so excited to get, they’re tagging me in this post.”

James: Was your own experience as a young designer at all like that?

Daniel: You know, my generation was obsessed with Alexander McQueen and the reboot of Helmut Lang. The idea of being unattainable and austere and in the glossy magazines was the aspiration when I was in school. Now I'm just trying to feel out this uncharted territory of being exceptionally attainable, very relatable, one-on-one communicating with these people who are inspired by and purchasing my work.

And it's so tangible, so relatable. Instead of being this $1,700, $75,000 crazy, one-of-a-kind, unaffordable piece, it's a $25 mask that this person is so excited to get, they're tagging me in this post. And then I'm sending them back a video message saying, “Thanks, this looks great,” and we're having a real, one-on-one connection.

What I'm finding the most exciting and heartwarming part about this Zero Waste Daniel journey is that I'm seeing a generation, an actual generation of designers, messaging me saying, “I’ve started this because of your brand. I saw a video about you and now I'm making patchwork.” All the way to, like, “My son is doing this too, I need something for my kids out of scraps.”

This is having that kind of impact. This is inspiring a new generation. This is that turning point inside the fashion industry, inside the apparel production industry, which is really much larger than the fashion industry. I’m both incredibly excited about and also super leery. Like, now I have to innovate on my own style. Make sure that I share transparently without giving everything away. It's such a tightrope walk all the time to be all the things, but also not give it all away.

I feel like with this, I'm so transparent and I'm so honest and I give so much information about it that people are like, “Well, show me how you sew it.” And I'm like, “Well, I'm not going to give you my patterns because those are mine.” And they're like, “Well, if you give me information about where it came from, then I should also know what the pattern is.”

James: You recently visited Uniqlo’s down recycling operation. What was that like?

Daniel: I always am a little leery of large-scale brands talking about what they're doing that's green. What I find so interesting about Uniqlo is their approach, and it's not the sourcing tactic. It's the building tactic. I was so inspired that rather than say, “OK, we'll just mine for more resources that are more sustainable,” they were like, “We have to stop using the down. How are we going to collect this material that we've already harvested so much, and then put it back into our own economy?”

I mean, I think the product itself is really cool and that's great, from a design perspective. But it’s also this mono brand that people have real access to, all over the world. I mean, Uniqlo is on Fifth Avenue. The rent must be insane, right? When you're able to cover that rent and build the entire store with your own branded products, that's the pinnacle of how big you can get in this industry.

James: Is this a one-off, or will there be more?

Daniel: There's a thing in the pipeline right now. I'd love to work with them again — it was such a great and really seamless process. But I think anything that's going to come next between us is going to take a lot longer because of the focused way that they approach doing something like that. They're not like, “Oh great, we got a couple rolls of fabric. Let's cut some shirts and tell people it's green.”

James: What will the rest of your day be like?

Daniel: Today is a banger day of production. We are working with a great contractor in Middle Village who took a bunch of patchwork and turned all of that into bucket hats for us this week. So I'm gonna pick up my bucket hats and check those out.

It's a really interesting time, because we hear every day about the jobs crisis, jobs, jobs, jobs. I've had a really hard time finding people who want to work. So, it's really heartwarming to find locals who have the skill set who want to work. I know people like AOC have talked about this concept of the Green New Deal. And I feel like that very much applies to my industry and what I'm doing. It's actually a phrase that I was using before I ever heard AOC use it. The idea of the New Deal was, like, you dig a ditch and then you fill it in. We have a mountain of scraps. So now we just have to turn it into stuff. And when we find qualified people who are inspired by and capable of doing this work, it's really, really exciting because there is a lot of work to do in this space. And we are actually, despite all odds, growing right now.

We have a lot of contractors, a lot of helpers, a lot of people in our network leave the city when this started and we're really, really excited to be building it back up. Every day is a little bit of production, a little bit of managing production, a little bit of customer service. And just, you know, trying to make it all happen in New York.